View on QuantumAI View on QuantumAI

|

Run in Google Colab Run in Google Colab

|

View source on GitHub View source on GitHub

|

|

try:

import cirq

except ImportError:

print("installing cirq...")

!pip install --quiet cirq

import cirq

print("installed cirq.")

Conceptual overview

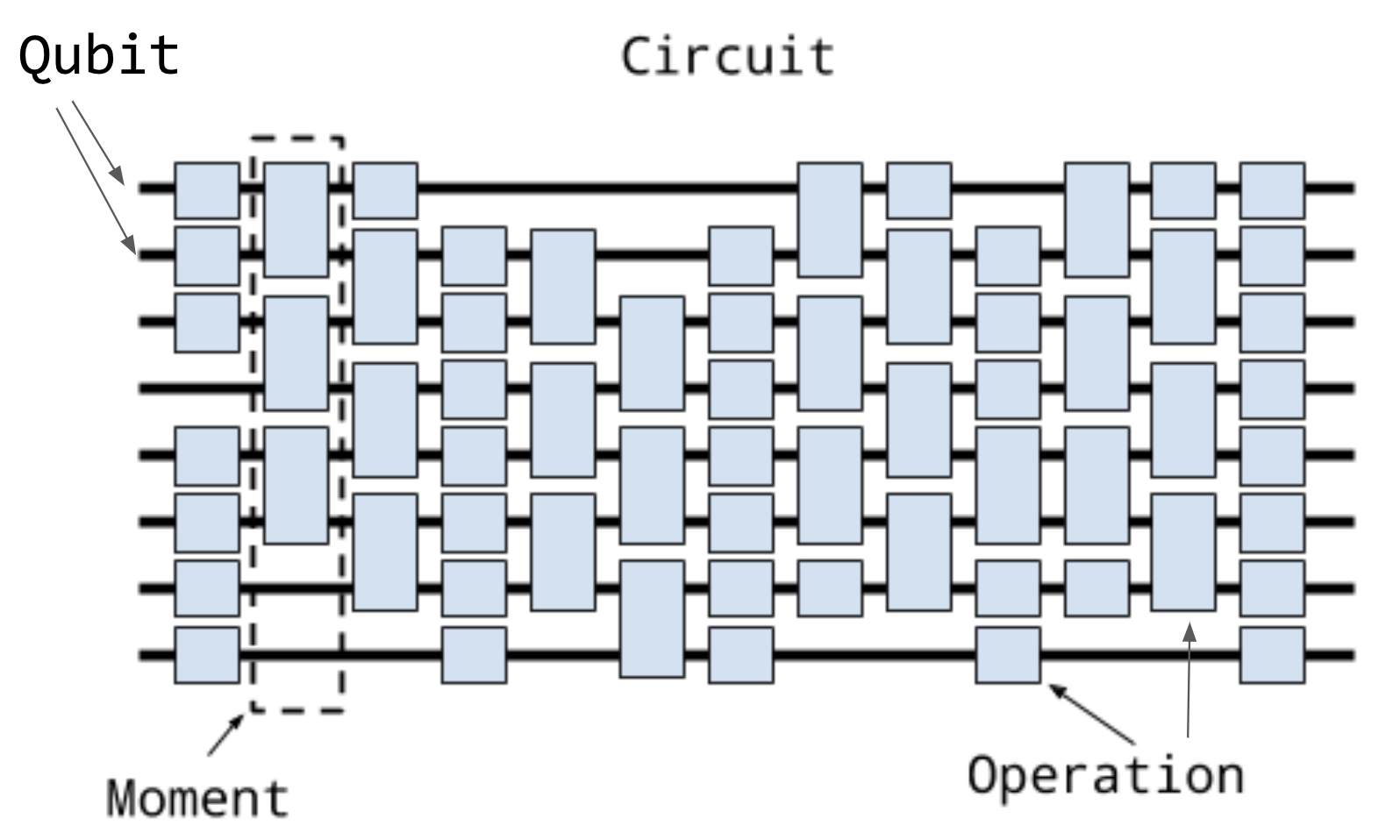

The primary representation of quantum programs in Cirq is the Circuit class. A Circuit is a collection of Moments. A Moment is a collection of Operations that all act during the same abstract time slice. An Operation is some effect that operates on a specific subset of Qubits; the most common type of Operation is a GateOperation.

Let's unpack this.

At the base of this construction is the notion of a qubit. In Cirq, qubits and other quantum objects are identified by instances of subclasses of the cirq.Qid base class. Different subclasses of Qid can be used for different purposes. For example, the qubits that Google’s devices use are often arranged on the vertices of a square grid. For this, the class cirq.GridQubit subclasses cirq.Qid. For example, you can create a 3 by 3 grid of qubits using:

qubits = cirq.GridQubit.square(3)

print(qubits[0])

print(qubits)

q(0, 0) [cirq.GridQubit(0, 0), cirq.GridQubit(0, 1), cirq.GridQubit(0, 2), cirq.GridQubit(1, 0), cirq.GridQubit(1, 1), cirq.GridQubit(1, 2), cirq.GridQubit(2, 0), cirq.GridQubit(2, 1), cirq.GridQubit(2, 2)]

The next level up is the notion of cirq.Gate. A cirq.Gate represents a physical process that occurs on a qubit. The important property of a gate is that it can be applied to one or more qubits. This can be done via the gate.on(*qubits) method itself or via gate(*qubits). Doing this turns a cirq.Gate into a cirq.Operation.

# This is a Pauli X gate. It is an object instance.

x_gate = cirq.X

# Applying it to the qubit at location (0, 0) (defined above)

# turns it into an operation.

x_op = x_gate(qubits[0])

print(x_op)

X(q(0, 0))

A cirq.Moment is simply a collection of operations, each of which operates on a different set of qubits, and which conceptually represents these operations as occurring during this abstract time slice. The Moment structure itself is not required to be related to the actual scheduling of the operations on a quantum computer or via a simulator, though it can be. For example, here is a Moment in which Pauli X and a CZ gate operate on three qubits:

cz = cirq.CZ(qubits[0], qubits[1])

x = cirq.X(qubits[2])

moment = cirq.Moment(x, cz)

print(moment)

╷ 0 1 2 ╶─┼─────── 0 │ @─@ X │

The above is not the only way one can construct moments, nor even the typical method, but illustrates that a Moment is just a collection of operations on disjoint sets of qubits.

Finally, at the top level, a cirq.Circuit is an ordered series of cirq.Moment objects. The first Moment in this series contains the first Operations that will be applied. Here, for example, is a simple circuit made up of two moments:

cz01 = cirq.CZ(qubits[0], qubits[1])

x2 = cirq.X(qubits[2])

cz12 = cirq.CZ(qubits[1], qubits[2])

moment0 = cirq.Moment([cz01, x2])

moment1 = cirq.Moment([cz12])

circuit = cirq.Circuit((moment0, moment1))

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───@───────

│

(0, 1): ───@───@───

│

(0, 2): ───X───@───

Note that the above is one of the many ways to construct a Circuit, which illustrates the concept that a Circuit is an iterable of Moment objects.

Constructing circuits

Constructing Circuits as a series of hand-crafted Moment objects is tedious. Instead, Cirq provides a variety of different ways to create a Circuit.

One of the most useful ways to construct a Circuit is by appending onto the Circuit with the Circuit.append method.

q0, q1, q2 = [cirq.GridQubit(i, 0) for i in range(3)]

circuit = cirq.Circuit()

circuit.append([cirq.CZ(q0, q1), cirq.H(q2)])

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───@───

│

(1, 0): ───@───

(2, 0): ───H───

This appended a new moment to the qubit, which you can continue to do:

circuit.append([cirq.H(q0), cirq.CZ(q1, q2)])

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───@───H───

│

(1, 0): ───@───@───

│

(2, 0): ───H───@───

These two examples appended full moments. What happens when you append all of these at once?

circuit = cirq.Circuit()

circuit.append([cirq.CZ(q0, q1), cirq.H(q2), cirq.H(q0), cirq.CZ(q1, q2)])

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───@───H───

│

(1, 0): ───@───@───

│

(2, 0): ───H───@───

This has again created two Moment objects. How did Circuit know how to do this? The Circuit.append method (and its cousin, Circuit.insert) both take an argument called strategy of type cirq.InsertStrategy. By default, InsertStrategy is InsertStrategy.EARLIEST.

InsertStrategies

cirq.InsertStrategy defines how Operations are placed in a Circuit when requested to be inserted at a given location. Here, a location is identified by the index of the Moment (in the Circuit) where the insertion is requested to be placed at (in the case of Circuit.append, this means inserting at the Moment, at an index one greater than the maximum moment index in the Circuit).

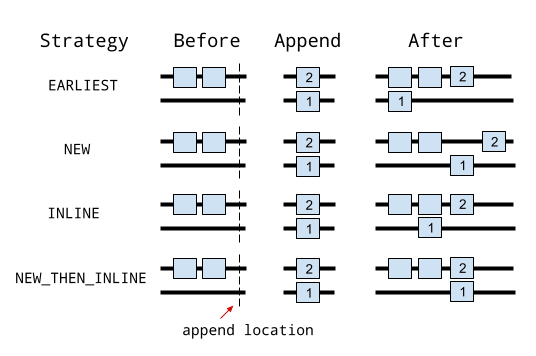

There are four such strategies: InsertStrategy.EARLIEST, InsertStrategy.NEW, InsertStrategy.INLINE and InsertStrategy.NEW_THEN_INLINE.

InsertStrategy.EARLIEST, which is the default, is defined as:

Scans backward from the insert location until a moment with operations touching qubits affected by the operation to insert is found. The operation is added to the moment just after that location.

For example, if you first create an Operation in a single moment, and then use InsertStrategy.EARLIEST, the Operation can slide back to this first Moment if there is space:

from cirq.circuits import InsertStrategy

circuit = cirq.Circuit()

circuit.append([cirq.CZ(q0, q1)])

circuit.append([cirq.H(q0), cirq.H(q2)], strategy=InsertStrategy.EARLIEST)

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───@───H───

│

(1, 0): ───@───────

(2, 0): ───H───────

After creating the first moment with a CZ gate, the second append uses the InsertStrategy.EARLIEST strategy. The H on q0 cannot slide back, while the H on q2 can and so ends up in the first Moment.

Contrast this with InsertStrategy.NEW that is defined as:

Every operation that is inserted is created in a new moment.

circuit = cirq.Circuit()

circuit.append([cirq.H(q0), cirq.H(q1), cirq.H(q2)], strategy=InsertStrategy.NEW)

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───H─────────── (1, 0): ───────H─────── (2, 0): ───────────H───

Here every operator processed by the append ends up in a new moment. InsertStrategy.NEW is most useful when you are inserting a single operation and do not want it to interfere with other Moments.

Another strategy is InsertStrategy.INLINE:

Attempts to add the operation to insert into the moment just before the desired insert location. But, if there’s already an existing operation affecting any of the qubits touched by the operation to insert, a new moment is created instead.

circuit = cirq.Circuit()

circuit.append([cirq.CZ(q1, q2)])

circuit.append([cirq.CZ(q1, q2)])

circuit.append([cirq.H(q0), cirq.H(q1), cirq.H(q2)], strategy=InsertStrategy.INLINE)

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───────H───────

(1, 0): ───@───@───H───

│ │

(2, 0): ───@───@───H───

After two initial CZ between the second and third qubit, the example inserts three H operations. The H on the first qubit is inserted into the previous Moment, but the H on the second and third qubits cannot be inserted into the previous Moment, so a new Moment is created.

Finally, InsertStrategy.NEW_THEN_INLINE is a useful strategy to start a new moment and then continue

inserting from that point onwards.

Creates a new moment at the desired insert location for the first operation, but then switches to inserting operations according to InsertStrategy.INLINE.

circuit = cirq.Circuit()

circuit.append([cirq.H(q0)])

circuit.append([cirq.CZ(q1, q2), cirq.H(q0)], strategy=InsertStrategy.NEW_THEN_INLINE)

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───H───H───

(1, 0): ───────@───

│

(2, 0): ───────@───

The first append creates a single moment with an H on the first qubit. Then, the append with the InsertStrategy.NEW_THEN_INLINE strategy begins by inserting the CZ in a new Moment (the InsertStrategy.NEW in InsertStrategy.NEW_THEN_INLINE). Subsequent appending is done InsertStrategy.INLINE, so the next H on the first qubit is appending in the just created Moment.

Here is a picture showing simple examples of appending 1 and then 2 using the different strategies

Patterns for arguments to append and insert

In the above examples, you used a series of Circuit.append calls with a list of different Operations added to the circuit. However, the argument where you have supplied a list can also take more than just list values. For instance:

def my_layer():

yield cirq.CZ(q0, q1)

yield [cirq.H(q) for q in (q0, q1, q2)]

yield [cirq.CZ(q1, q2)]

yield [cirq.H(q0), [cirq.CZ(q1, q2)]]

circuit = cirq.Circuit()

circuit.append(my_layer())

for x in my_layer():

print(x)

CZ(q(0, 0), q(1, 0)) [cirq.H(cirq.GridQubit(0, 0)), cirq.H(cirq.GridQubit(1, 0)), cirq.H(cirq.GridQubit(2, 0))] [cirq.CZ(cirq.GridQubit(1, 0), cirq.GridQubit(2, 0))] [cirq.H(cirq.GridQubit(0, 0)), [cirq.CZ(cirq.GridQubit(1, 0), cirq.GridQubit(2, 0))]]

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───@───H───H───────

│

(1, 0): ───@───H───@───@───

│ │

(2, 0): ───H───────@───@───

Recall that Python functions with a yield are generators. Generators are functions that act as iterators. The above example iterates over my_layer() with a for loop. In this case, each of the yields produces:

Operations,- lists of

Operations, - or lists of

Operationsmixed with lists ofOperations.

When you pass an iterator to the append method, Circuit is able to flatten all of these and pass them as one giant list to Circuit.append (this also works for Circuit.insert).

The above idea uses the concept of cirq.OP_TREE. An OP_TREE is not a class, but a contract. The basic idea is that, if the input can be iteratively flattened into a list of operations, then the input is an OP_TREE.

A very nice pattern emerges from this structure: define generators for sub-circuits, which can vary by size or Operation parameters.

Another useful method to construct a Circuit fully formed from an OP_TREE is to pass the OP_TREE into Circuit when initializing it:

circuit = cirq.Circuit(cirq.H(q0), cirq.H(q1))

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───H─── (1, 0): ───H───

Slicing and iterating over circuits

Circuits can be iterated over and sliced. When they are iterated, each item in the iteration is a moment:

circuit = cirq.Circuit(cirq.H(q0), cirq.CZ(q0, q1))

for moment in circuit:

print(moment)

╷ 0 ╶─┼─── 0 │ H │ ╷ 0 ╶─┼─── 0 │ @ │ │ 1 │ @ │

Slicing a Circuit, on the other hand, produces a new Circuit with only the moments corresponding to the slice:

circuit = cirq.Circuit(cirq.H(q0), cirq.CZ(q0, q1), cirq.H(q1), cirq.CZ(q0, q1))

print(circuit[1:3])

(0, 0): ───@───────

│

(1, 0): ───@───H───

Two especially useful applications of this are dropping the last moment (which are often just measurements): circuit[:-1], and reversing a circuit: circuit[::-1].

Nesting circuits with CircuitOperation

Circuits can be nested inside one another with cirq.CircuitOperation. This is useful for concisely defining large, repetitive circuits, as the repeated section can be defined once and then be reused elsewhere. Circuits that need to be serialized especially benefit from this, as loops and functions used in the Python construction of a circuit are otherwise not captured in serialization.

The subcircuit must first be "frozen" to indicate that no further changes will be made to it.

subcircuit = cirq.Circuit(cirq.H(q1), cirq.CZ(q0, q1), cirq.CZ(q2, q1), cirq.H(q1))

subcircuit_op = cirq.CircuitOperation(subcircuit.freeze())

circuit = cirq.Circuit(cirq.H(q0), cirq.H(q2), subcircuit_op)

print(circuit)

[ (0, 0): ───────@─────────── ]

[ │ ]

(0, 0): ───H───[ (1, 0): ───H───@───@───H─── ]───

[ │ ]

[ (2, 0): ───────────@─────── ]

│

(1, 0): ───────#2────────────────────────────────

│

(2, 0): ───H───#3────────────────────────────────

Frozen circuits can also be constructed directly, for convenience.

circuit = cirq.Circuit(

cirq.CircuitOperation(

cirq.FrozenCircuit(cirq.H(q1), cirq.CZ(q0, q1), cirq.CZ(q2, q1), cirq.H(q1))

)

)

print(circuit)

[ (0, 0): ───────@─────────── ]

[ │ ]

(0, 0): ───[ (1, 0): ───H───@───@───H─── ]───

[ │ ]

[ (2, 0): ───────────@─────── ]

│

(1, 0): ───#2────────────────────────────────

│

(2, 0): ───#3────────────────────────────────

A CircuitOperation is sort of like a function: by default, it will behave like the circuit it contains, but you can also pass arguments to it that alter the qubits it operates on, the number of times it repeats, and other properties. CircuitOperations can also be referenced multiple times within the same "outer" circuit for conciseness.

subcircuit_op = cirq.CircuitOperation(cirq.FrozenCircuit(cirq.CZ(q0, q1)))

# Create a copy of subcircuit_op that repeats twice...

repeated_subcircuit_op = subcircuit_op.repeat(2)

# ...and another copy that replaces q0 with q2 to perform CZ(q2, q1).

moved_subcircuit_op = subcircuit_op.with_qubit_mapping({q0: q2})

circuit = cirq.Circuit(repeated_subcircuit_op, moved_subcircuit_op)

print(circuit)

[ (0, 0): ───@─── ]

(0, 0): ───[ │ ]────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

[ (1, 0): ───@─── ](loops=2)

│

(1, 0): ───#2─────────────────────────────#2──────────────────────────────────────────────────

│

[ (0, 0): ───@─── ]

(2, 0): ──────────────────────────────────[ │ ]─────────────────────────────────

[ (1, 0): ───@─── ](qubit_map={q(0, 0): q(2, 0)})

For the most part, a CircuitOperation behaves just like a regular Operation: its qubits are the qubits of the contained circuit (after applying any provided mapping), and it can be placed inside any Moment that doesn't already contain operations on those qubits. This means that CircuitOperations can be used to represent more complex operation timing, such as three operations on one qubit in parallel with two operations on another:

subcircuit_op = cirq.CircuitOperation(cirq.FrozenCircuit(cirq.H(q0)))

circuit = cirq.Circuit(

subcircuit_op.repeat(3), subcircuit_op.repeat(2).with_qubit_mapping({q0: q1})

)

print(circuit)

(0, 0): ───[ (0, 0): ───H─── ](loops=3)─────────────────────────────────

(1, 0): ───[ (0, 0): ───H─── ](qubit_map={q(0, 0): q(1, 0)}, loops=2)───

In the above example, even though the top CircuitOperation is iterated three times and the bottom one is iterated two times, they still reside within the same Moment, meaning they can be thought of conceptually as executing simultaneously in the same time step. However, this may not hold when the circuit is run on hardware or a simulator.

CircuitOperations can also be nested within each other to arbitrary depth.

qft_1 = cirq.CircuitOperation(cirq.FrozenCircuit(cirq.H(q0)))

qft_2 = cirq.CircuitOperation(cirq.FrozenCircuit(cirq.H(q1), cirq.CZ(q0, q1) ** 0.5, qft_1))

qft_3 = cirq.CircuitOperation(

cirq.FrozenCircuit(cirq.H(q2), cirq.CZ(q1, q2) ** 0.5, cirq.CZ(q0, q2) ** 0.25, qft_2)

)

# etc.

Finally, the mapped_circuit method will return the circuit that a CircuitOperation represents after all repetitions and remappings have been applied. By default, this only "unrolls" a single layer of CircuitOperations. To recursively unroll all layers, you can pass deep=True to this method.

# A large CircuitOperation with other sub-CircuitOperations.

print('Original qft_3 CircuitOperation')

print(qft_3)

# Unroll the outermost CircuitOperation to a normal circuit.

print('Single layer unroll:')

print(qft_3.mapped_circuit(deep=False))

# Unroll all of the CircuitOperations recursively.

print('Recursive unroll:')

print(qft_3.mapped_circuit(deep=True))

Original qft_3 CircuitOperation

[ [ (0, 0): ───────@───────[ (0, 0): ───H─── ]─── ] ]

[ (0, 0): ───────────────@────────[ │ ]─── ]

[ │ [ (1, 0): ───H───@^0.5───────────────────────── ] ]

[ │ │ ]

[ (1, 0): ───────@───────┼────────#2────────────────────────────────────────────────── ]

[ │ │ ]

[ (2, 0): ───H───@^0.5───@^0.25─────────────────────────────────────────────────────── ]

Single layer unroll:

[ (0, 0): ───────@───────[ (0, 0): ───H─── ]─── ]

(0, 0): ───────────────@────────[ │ ]───

│ [ (1, 0): ───H───@^0.5───────────────────────── ]

│ │

(1, 0): ───────@───────┼────────#2──────────────────────────────────────────────────

│ │

(2, 0): ───H───@^0.5───@^0.25───────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Recursive unroll:

(0, 0): ───────────────@────────────@───────H───

│ │

(1, 0): ───────@───────┼────────H───@^0.5───────

│ │

(2, 0): ───H───@^0.5───@^0.25───────────────────

Summary

Circuits are sliceable iterables of Moments, which are sliceable iterables of Operations, which are Gates applied to Qubits. Cirq provides intuitive and flexible ways to construct, add to, divide, and nest Circuits, with generators, slicing, and CircuitOperations.

Knowing how to create a circuit is useful, but what you put into a circuit is the interesting part. Read more about these constituent structures at:

- Qubits - the software representation of quantum bits

- Gates - quantum gates that become operations when applied to qubits

- Operators - more complicated structures to put in circuits

Once you've built your circuit, read these to learn what you can do with it:

- Simulation - run your circuit on the Cirq simulator to see what it does

- Quantum Virtual Machine - run your circuit on a specialized simulator that mimics actual quantum hardware, including noise.

- Transform circuits - run transformer functions to change your circuit in different ways

If you need to import or export circuits into or out of Cirq, see:

- Import/export circuits - features to serialize/deserialize circuits into/from different formats